“Caipira music is something that leaves inside us. It’s not a question of fashion, but of being passionate for the race, for the land.”

Inezita Barroso (Folha de S.Paulo, Ilustrada, March 6, 2005)

Seção de vídeo

The researcher

Teenager register

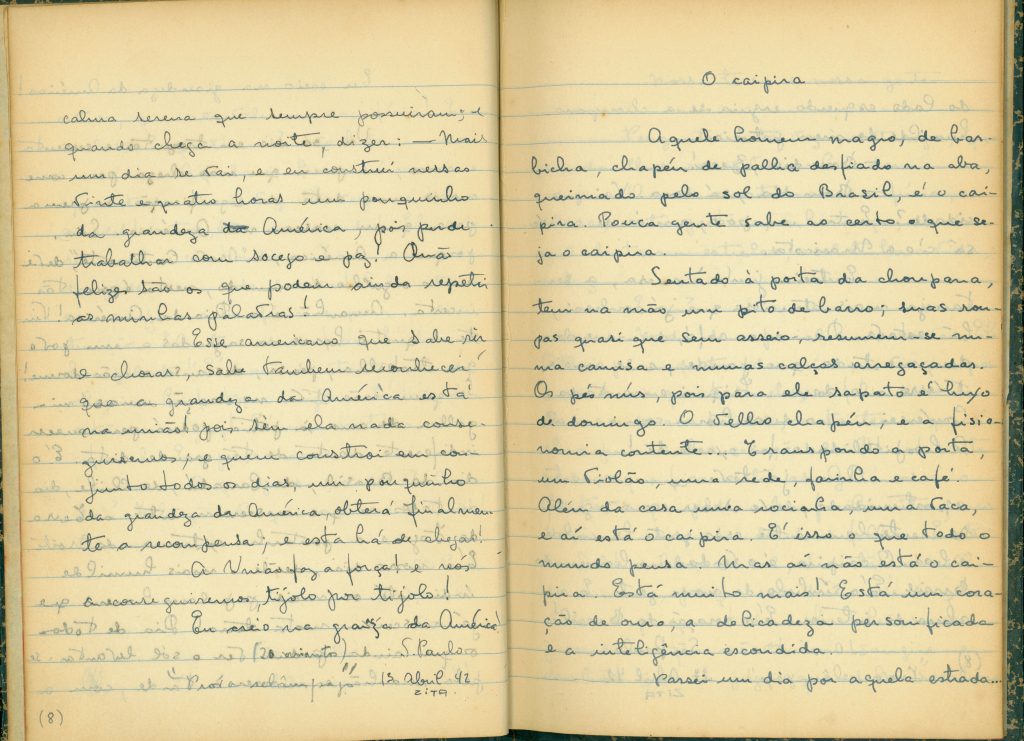

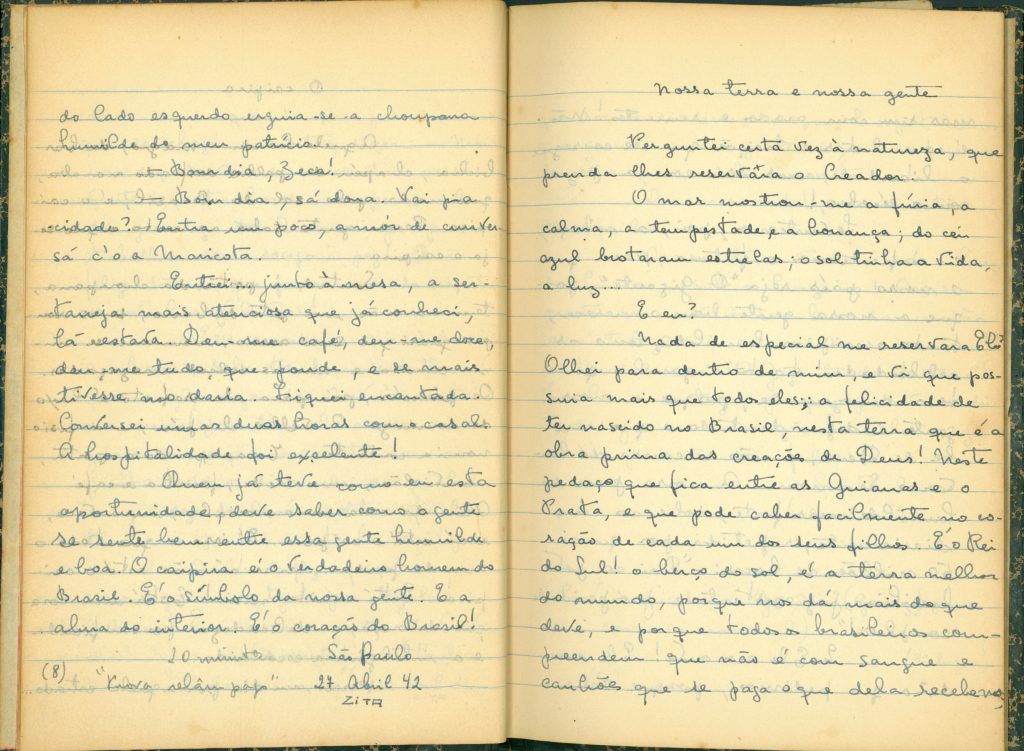

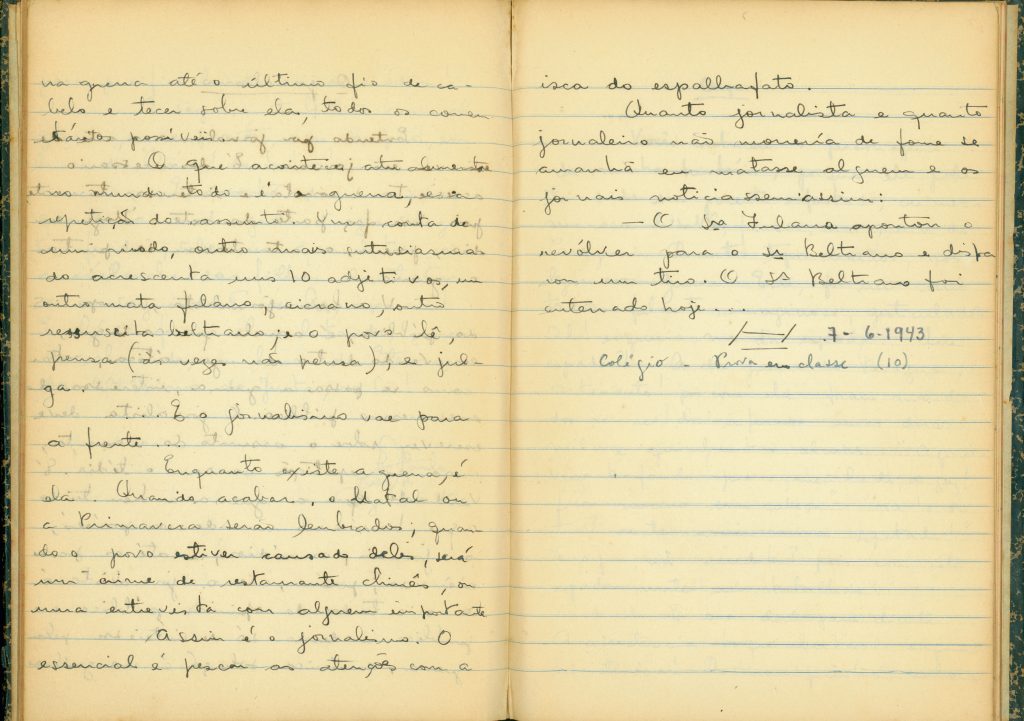

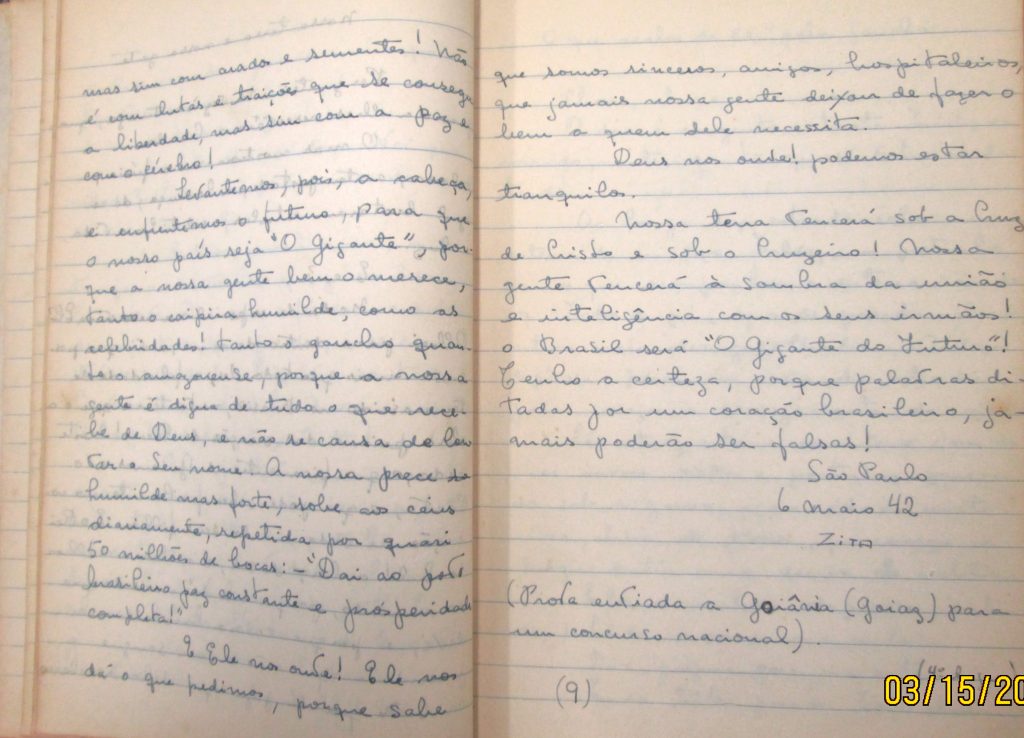

Notebook with Inezita’s registers from the 1940s. She described them as follows: “Chronicles… Nonsenses… Tests… Careless verses… Will to fill in the blanks”. Texts bring information that stand out the singer’s dedication to research.

1/10

“Nobody has the right to stop us and I never had a bad time. As a professional, I’m accomplished; as an artist, I’m not.”

Inezita Barroso (Folha da Tarde, August 14, 1974)

Inezita Barroso, the life [Chapter: The researcher]

By Paulo Freire*

* Curator of Ocupação Inezita Barroso, Paulo Freire tells the story of a 90-year-old lifetime, full of music and storytelling. Divided into six chapters (The girl, The family, The artist, The researcher, Ohh, how I love this show! and A legacy), the narratives spread through the site, mapping the life of one of the most important artists of Brazilian popular culture. Welcome to the beginning of this beautiful journey.

Easy, dear friends who supported me up to this moment. Can you, ladies and gentlemen, imagine a young Brazilian artist, in her heydays of fame and glory, spoiled by everyone, being awarded the most important singing prizes, getting out of her comfort zone and stardom to plunge in an adventure of a long trip by car? For this journey, she managed to get a Jeep. She left São Paulo with her brother-in-law Maurício Barroso and the actor Nelson Camargo. However, none of her two friends could drive…

Folks, pay attention: Inezita Barroso left São Paulo driving a jeep through Brazilian highways in 1957, together with two men, as far as Belém!

In the interview with Aloísio Milani, she said: “I wanted to reach Rio Grande do Norte, preferably through the coastline. There were no roads, we got to the beach and drove by the sand. If there was a big tall cliff invading the sea, we’d go inland for about 100 kilometers in order to surround it and surpass the rock”.

In this trip, she could collect songs on the way, nurturing her passion for popular culture. A month and a half after departure, already at Paraíba, she received the message through an amateur radio saying she needed to return to São Paulo. She would be awarded best singer once again at Prêmio Roquete Pinto. She returned from the adventure directly to the award ceremony at Teatro Cultura Artística, in São Paulo capital.

The trip was of utmost importance to ensure Inezita would go deep in the countryman culture, getting to know the differences between the regions, writing down the songs, reinforcing the importance of the guitar in the meetings on the road, singing with truck drivers by the roadside and in small cities of Brazilian countryside.

In 1961, she quit Record. Little by little she was stepping aside TV and radio issues, for she was desappointed with the new prospect of Brazilian television, which was focusing on variety programs, losing sight of artistic projects. Although invited, se refused to be a part of that type of programs.

Inezita started, though, a new stage of her life. Decided to stay closer to her daughter and family. “My daughter is growing up and needs me”, she said. Started to give guitar classes in São Paulo (“from 8 in the morning up to midnight!”). During her vacations, she traveled with the family to São Vicente, at São Paulo coastline, but kept on giving classes. She had up to 60 students. Made pottery, formed choirs.

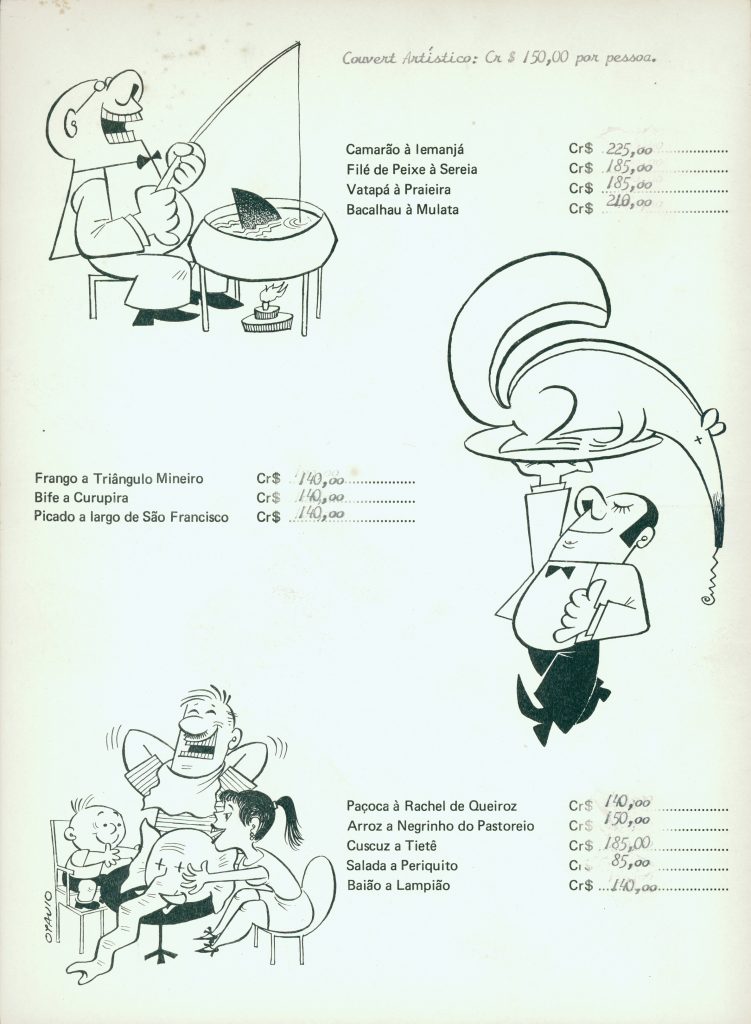

Opened the restaurant Casa de Inezita, at Avenida Santo Amaro. She dreamed about making a folk school of that place, with culinary classes and marketing of Brazilian craftsmanship. The restaurant interior design was set with objects she collected on popular culture. The menu included typical dishes.

She gave folk classes. Continued recording albums, always focusing on the repertoire of her researches. She used to say: “I like to record traditional music, of unknown artists… Do not take traditional for old, since folk music is in constant transformation”.

In 1969, the press started to announce “the return of Inezita” in the artist world, with shows, recitals. It was as if there was a need to have her back in the artistic scene: herself and all she represented. The invitations for show increased. She made presentations in up to 120 cities in the countryside of São Paulo in 1977, as well as in 1978. During this road trips, she attended the popular celebrations she so much loved, understanding that the music inside her belonged there.

At the same time she went back on stage, Inezita stated she would not go back to television scene, despite all the invitations. She saw an obscure future in television schedule. “I won’t sing any more to the red light of a cold machine, which broadcasts the show to a mass audience who enjoys only trendy music. Humble people fell my songs and don’t have a TV set. Therefore, singing in the Municipal Theater has the same importance as singing in the circus of the neighborhood or countryside to me”, she declared in an interview.

“One of the most important things, among many others, that I learned and understood was the origin of machismo in Brazilian folk manifestations. The woman rarely sings, but clap hands. The man is the one who always dances and appears good looking […].”

Inezita Barroso (Inezita Barroso, a História de uma Brasileira, by Arley Pereira)

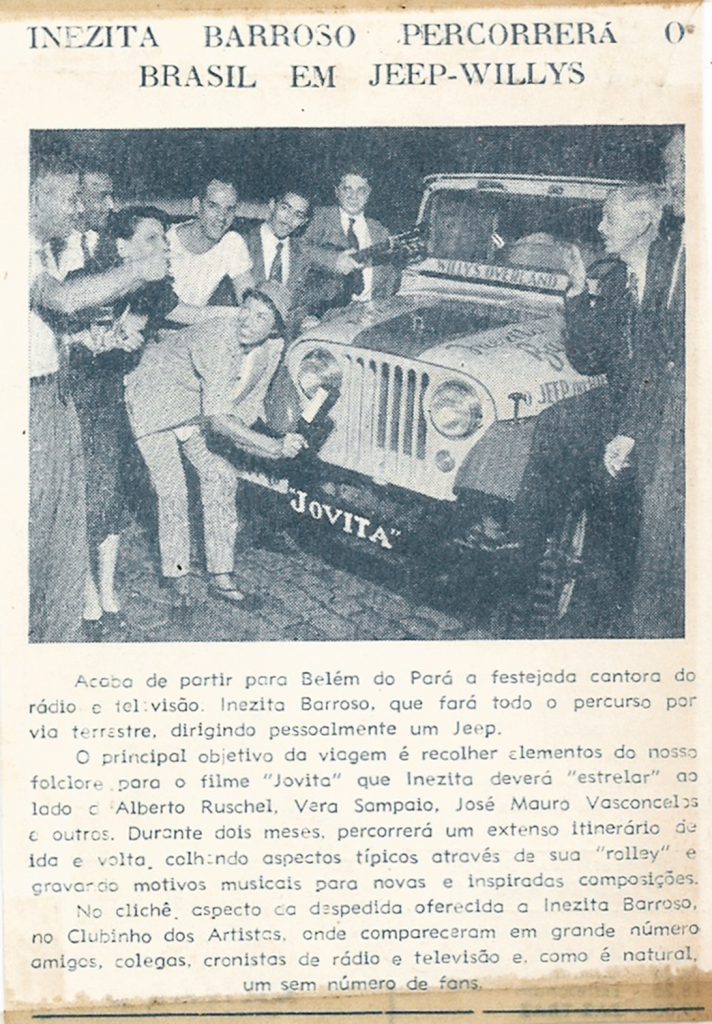

The trip

Newspapers registered Inezita’s trip to the northeast of Brazil in 1957, driving a jeep Jovita together with her friend Nelson Camargo e and her brother-in-law Maurício Barroso. The trip aimed at researching on regional music and folk manifestations, in order to build the character Jovita in a movie that was never shot. The movie would tell the story of a young woman from Ceará, who dressed like a man to fight in the Uruguay war (1864-1870) | picture: Revista Sete Dias na TV and Revista do Globo / personal collection

1/10

Seção de vídeo

Brief story on the trip by jeep

Image provided by Fundação Padre Anchieta (TV Cultura) to Ocupação Inezita Barroso

Saint Inezita

By Myriam Taubkin

In my carreer as musical producer and curator, I dedicated a long period to the Brazilian viola, its artists and traditions. In the process, I was able to assure Inezita Barroso’s importance. Her “sertaneja” soul – expressed in her chats, readings, trips, researches, and above all in the guidance chosen to her show Viola, Minha Viola – highlights how much he represented an oasis to those who played and loved the viola in Brazil.

Either the audience or the professionals identified Inezita as a safe harbor to everything concerning “caipira” culture. Her presence stimulated the enchantment we had with Brazilian countryside from last century, in the small details, in clichés – the wood-burning stove, the manioc plantation, the straw cigarette, the horse riding, the cattle grazing, the cheese on the table, the land road –, and in being proud of it.

Inezita looked forward to find composers, musicians, poets, singers and writers from this Brazil she loved and about which she longed to learn more. She made de acquaintance of our country as few people did; she loved to travel, to browse, to enter the radio stations of every village, to chat with local people, to discover new players and unknown composer. Her weekly show has this meaning, was open to all “caipira’s” branches.

I was lucky I’ve met her and have been with her in several situations. One of them was in the night of the pre-release of the book and documentary, Violeiros do Brasil. I decided to introduce them to the artists in a party at home. Inezita, who gave me the honor of writing the preface of the book, was also invited. Her arrival at my apartment caused a commotion among the employees and neighbors. Those who saw her passing by greeted her, smiled and cried. Such a thing happened only with Dominguinhos. These kind of people let our guard down, inspire us and give us the impression that they have always been part of the family.

Recently, I was at Viola, Minha Viola show among the audience, observing their behavior. I could see all kind of fans – those that thanked God for the opportunity of being there for the first time – after 30 years –, and those who hadn’t missed a show.

I remember also having gone with her to Pena Branca’s seventh day mass. Her arrival at Jaçanã’s church touched deeply the audience; it was as if she was embracing everybody in such an important moment. This comprehension was something natural of her character.

I don’t forget Braz da Viola, from Paulo Freire, and the stories about São Gonçalo, violeiros’s saint. Inezita had a collection of these saints at home. Like São Gonçalo, she loved to dance, sing, party, meet people. Like the saint, she loved to eat and drink, laugh out loud and always play the viola.

Isn’t she Saint Inezita, the patroness of Brazilian “violeiros”?

Myriam Taubkin is an artistic producer and curator. Specialized in Brazilian music, leads Projeto Memória Brasileira since 1987 and has already released the books and documentaries O Brasil da Sanfona (2004), Violões do Brasil (2005), Um Sopro de Brasil (2006) and Violeiros do Brasil (2008).

“I began unconsciously and, in a twenty-year career, I sum up to forty of researches. That’s why I regret leaving aside one thing to start another, for there is no conditions at all.”

Inezita Barroso (Folha da Tarde, 14 August, 1974)