image: João Pires/Estadão Conteúdo

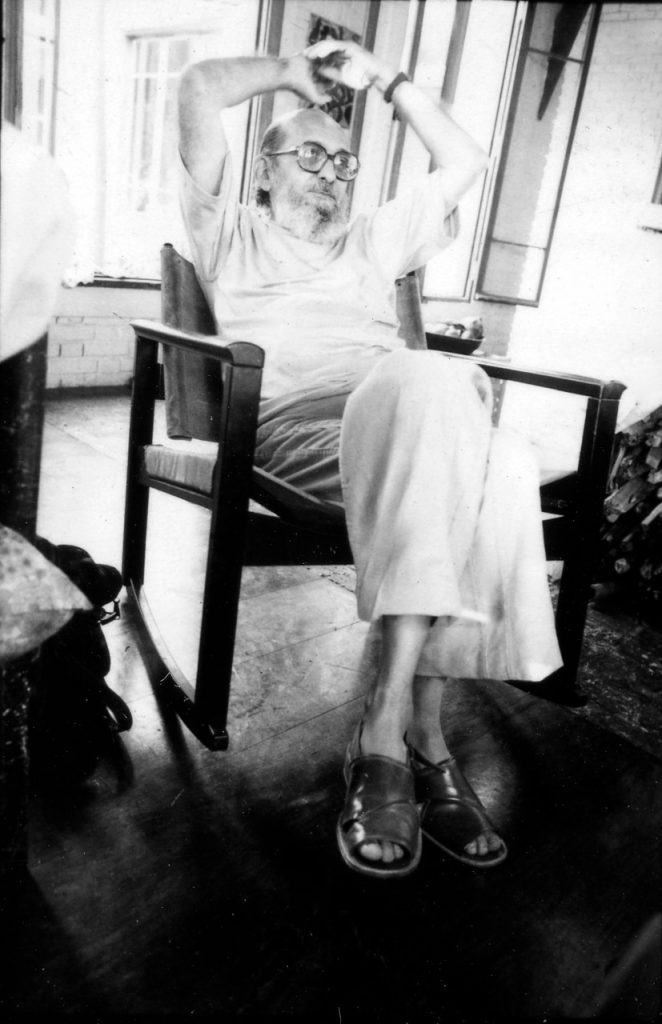

On April 1, 1964, the then president of Brazil João Goulart (1919–1976), who had been elected in 1961, was deposed by the military. The dictatorship was to last until March 15, 1985, marked by the suppression of political rights and the persecution of those who opposed it. Already in the early days of the civil-military dictatorship, Paulo Freire became an example of this sort of oppression.

In that very month of April, a commission of the University of Recife, where the educator worked, demanded that he give a report about his activities, in conformance with the new government policies. After Paulo gave his answers, on June 16 he was brought from his house to the barracks of the 4th Army, where he was detained. He was interrogated, released on July 3, and arrested again on the following day. He then remained in prison for nearly two months.

When freed, he was forced into exile, first in Bolivia, then in Chile. It was in the latter country that, in 1968, the educator wrote Pedagogia do oprimido. In 1969 and 1970, he was a visiting professor of the University of Harvard, in the United States. In 1970, when he published the book he had written in Chile, he became a professor at the University of Geneva, in Switzerland. Later, between 1975 in 1979, he founded, with other exiled Brazilians, the Cultural Action Institute (Idac), for educational services to Third World countries, while also leading programs of education and the teaching of literacy in Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Angola and St. Thomas and Príncipe, in Africa.

Paulo did not return to Brazil until 1980.

image: João Pires/Estadão Conteúdo

“Ricardo Kotscho – Paulo, and you, what did you do to pass the 75 days in prison?

Paulo Freire – it is profoundly absurd, a challenge to the mind, to learn to use the imagination, to see, to confirm once again, that it is not through ideas, through imagination, that you become free, but rather through the overcoming of concrete things. I could fly in my imagination, but my body stayed where it was.

Later they brought me outside my cell and I learned with my companions how to continue to care for my body, because, by caring for the body, one is necessarily caring for the mind, and I learned how to dominate my anxiety, for example.”

(Essa escola chamada vida, interview of Paulo Freire and Frei Betto conducted by Ricardo Kotscho, page 52)

For me, exile was profoundly educational. When, as an exiled person, I gained distance from Brazil, I began to better understand myself, as well as my country.

(“Essa escola chamada vida,” interview of Paulo Freire and Frei Betto conducted by Ricardo Kotscho, page 56)

“Paulo Freire – I gained asylum in the Bolivian embassy. I then went to La Paz. I stayed there one month, and a coup d’état took place there also, so I went to Chile.

That’s where my experience of exile began. The exile began in political asylum, at the embassy. As it turns out, the first sensation in the embassy is one of freedom. It’s funny! The body is actually confined, still. Because it is inside only the space of the embassy. That is the space of your freedom.

But the fact that you know that tomorrow you will fly on a plane to a place of exile gives you a sense of great freedom. So, you enjoy your freedom. Really… you enjoy freedom.

I felt a profound yearning for freedom, in my prison experience, in the situation of asylum, and during exile. Because, when you leave exile, you enlarge the universe of freedom even while you accept the tremendous restriction in your freedom by returning home. What is an exiled person? It is the guy who does not have the right to return home. And the interesting thing is: I spent nearly 16 years in exile without any chance of having the experience of going home at 5 o’clock.”

(“Essa escola chamada vida,” interview of Paulo Freire and Frei Betto conducted by Ricardo Kotscho, page 53)

by Sérgio Haddad*

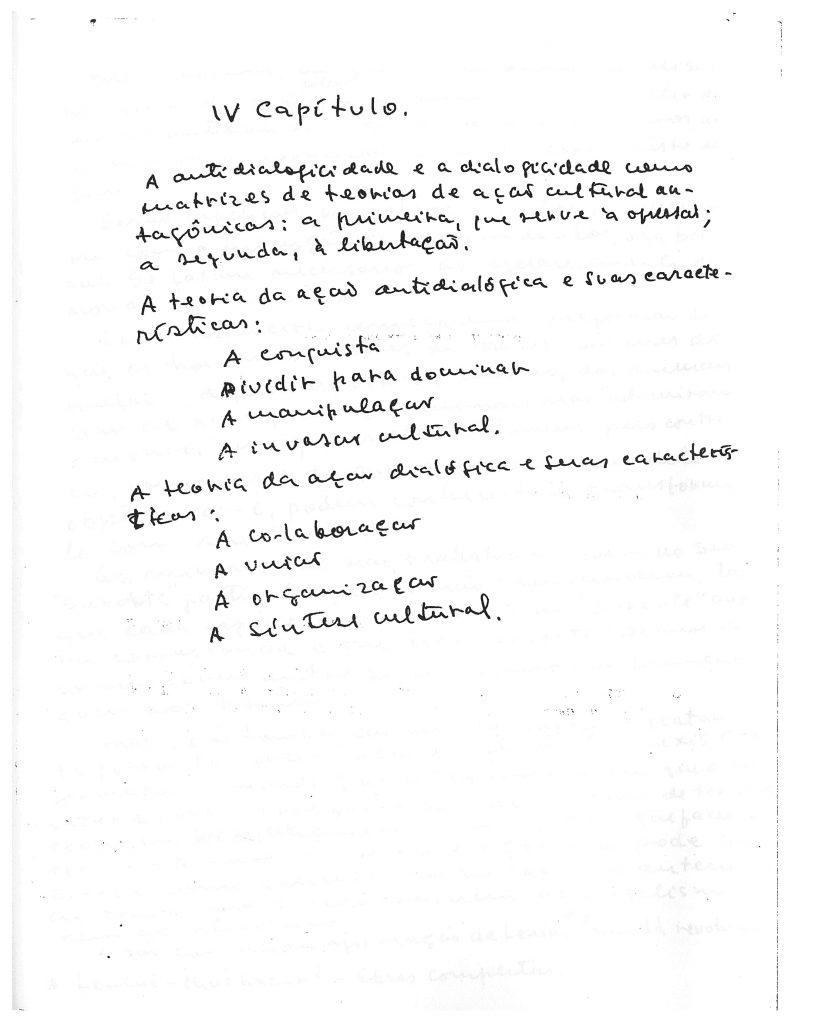

“Once the revision phase was complete, he received a bit of advice from social and political scientist Josué de Castro on one of the walks they often took through the parks of Santiago: to leave the original texts ‘resting’ in his desk drawer for several months. It was a way of distancing himself a little from what he had written. When he decided to go back to the text, he read it with enthusiasm, all at one go. He rewrote a few things, but felt the lack of a fourth chapter to round off the work. He then spent the next months writing it.”

Sérgio Haddad holds a degree in economics and pedagogy, and a PhD from the University of São Paulo (USP). A former professor in the Postgraduate Program in the Education of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP) and of the University of Caxias do Sul, he is currently participating in the coordination of the NGO Ação Educativa. A senior CNPq researcher, he recently released the book O Educador: um perfil de Paulo Freire published by Todavia.

*The cited passage is an excerpt from O educador, um perfil de Paulo Freire.

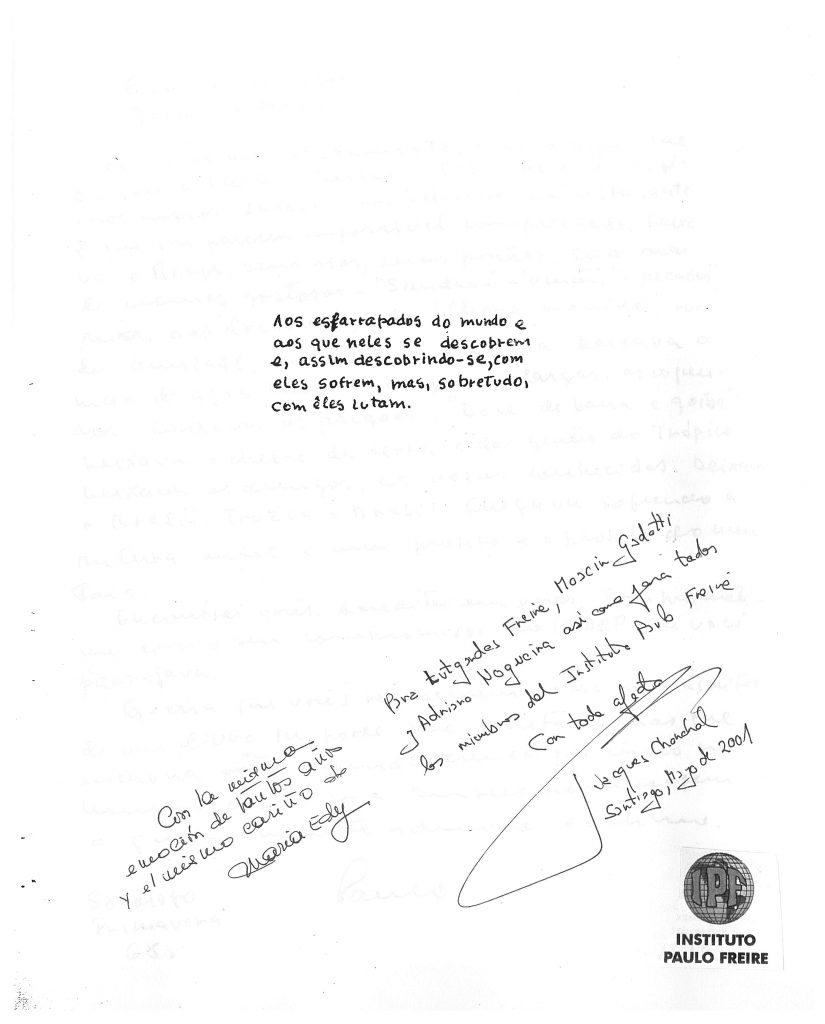

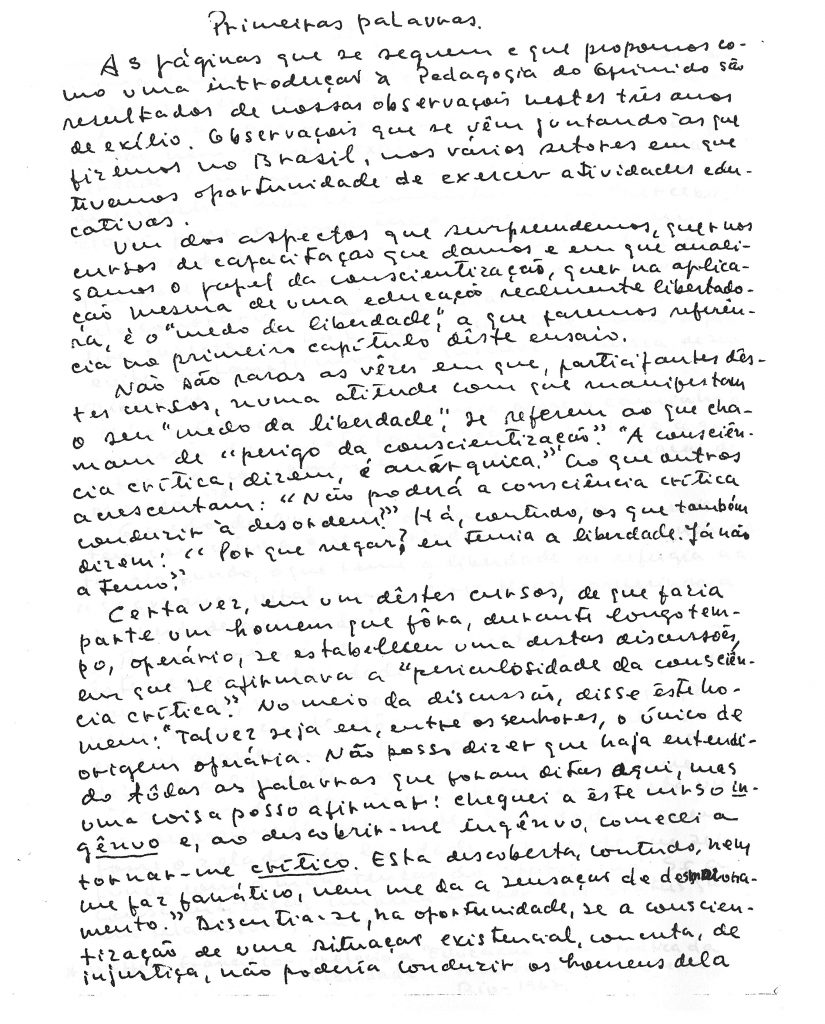

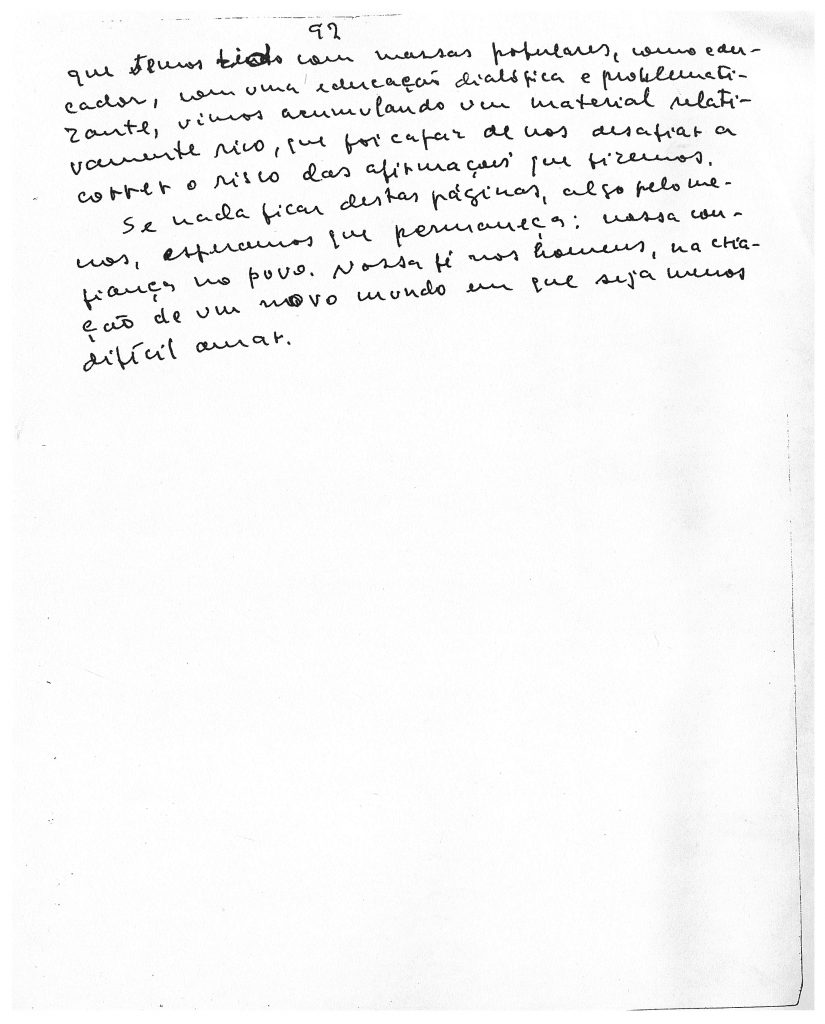

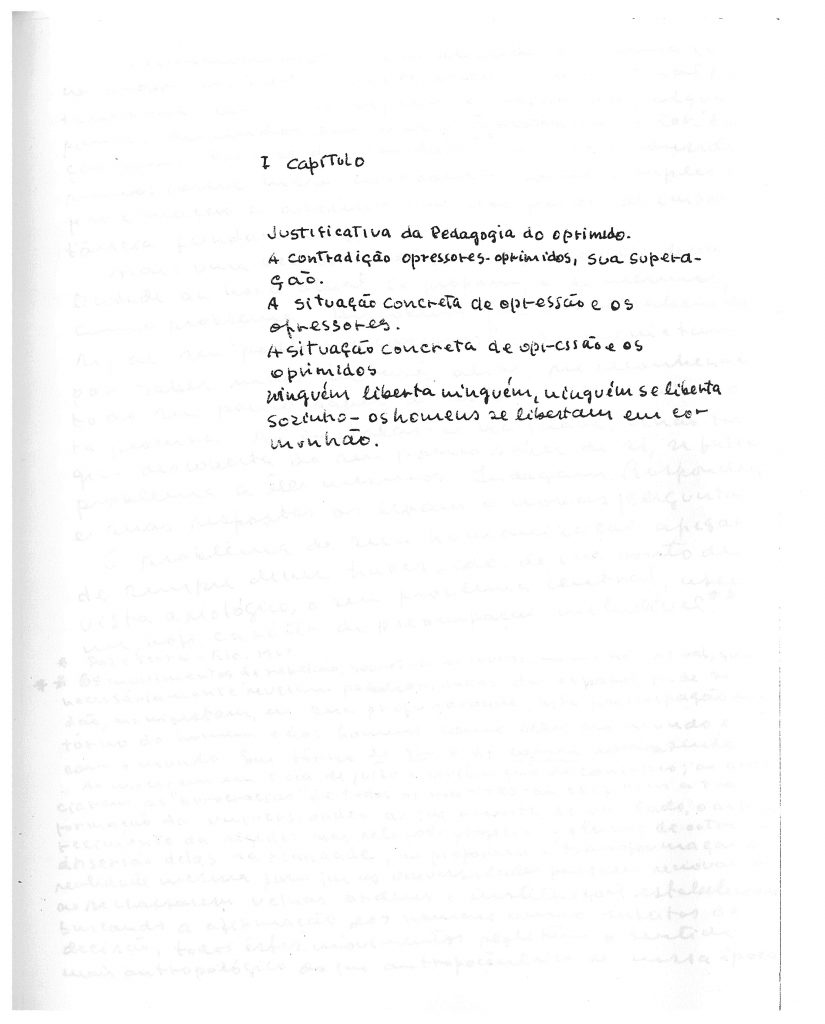

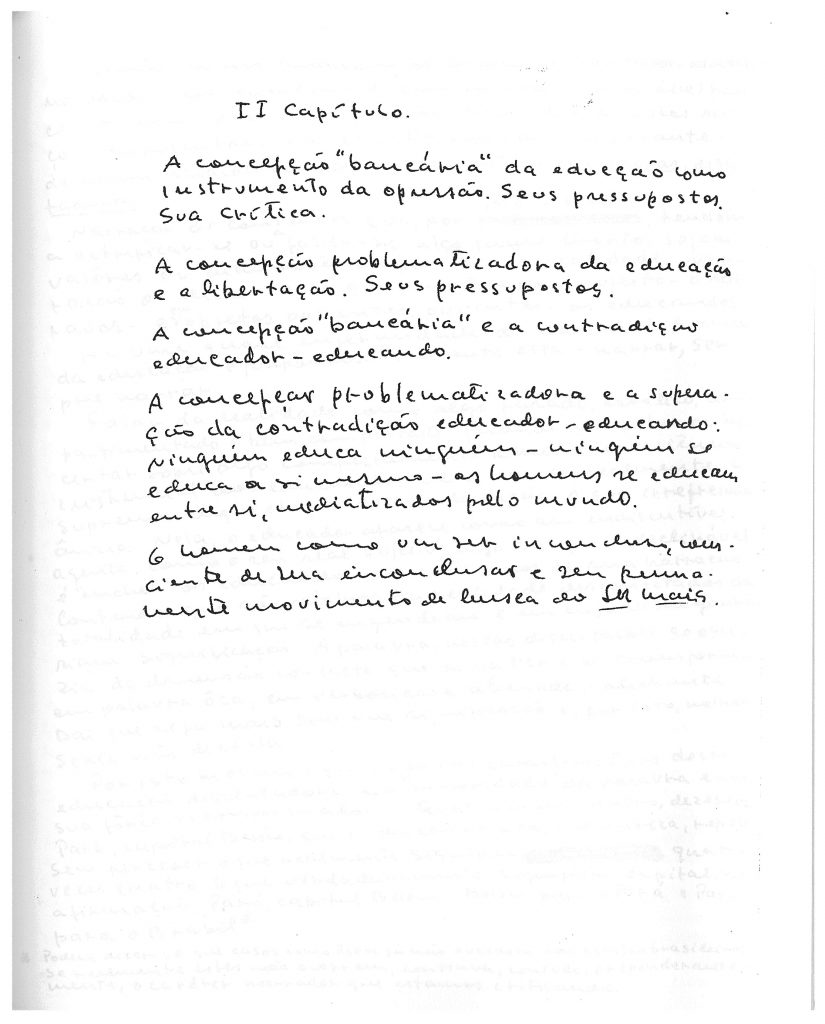

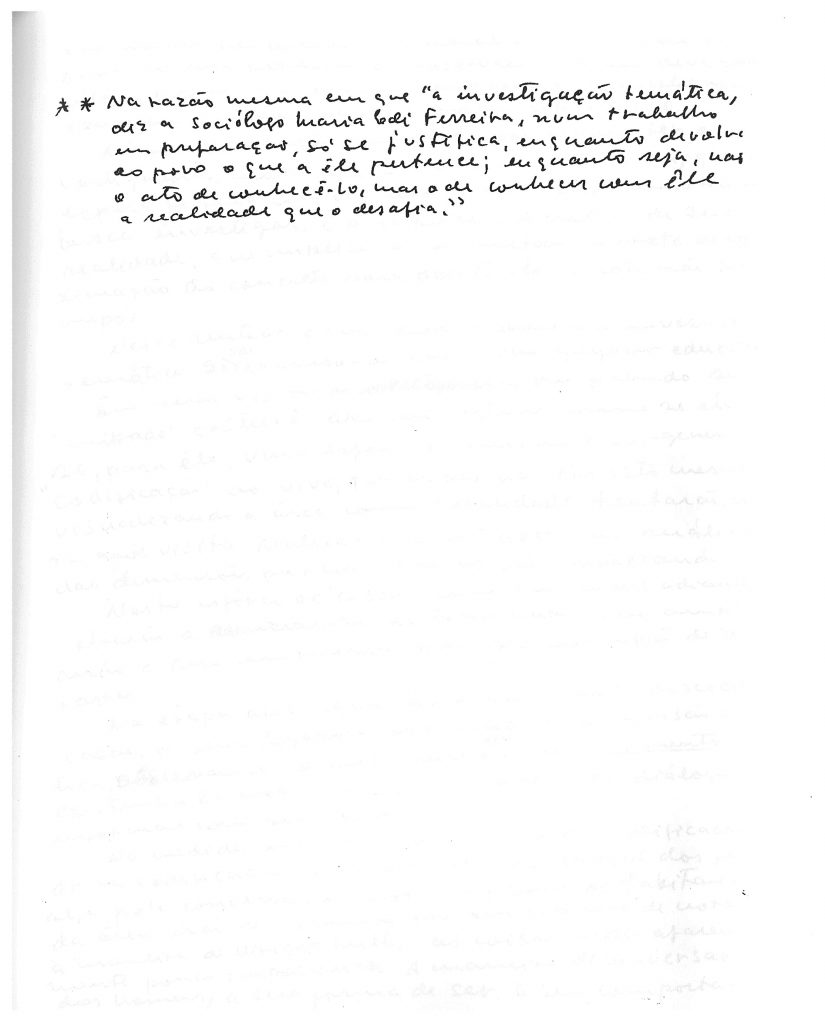

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

Manuscrito de "Pedagogia do Oprimido"

1/10

by Sérgio Haddad*

“His trip to the United States was a great challenge for Paulo. He resisted the idea at first – he thought that there was nothing he could learn, and much less teach in that place that he identified as the heart of imperialism. He was convinced by Elza, who understood her husband’s position as sectarian, since the entire population of that country could not be considered imperialist. […] When Paulo arrived in the United States, he managed to read in English with assuredness, but understood and spoke little of the language. At a certain moment, he commented to his wife: ‘Elza, I think that I have put myself into a dishonest, disloyal position, because I accepted an invitation, but I don’t speak the language here, and I cannot give classes in Portuguese! There is no way, and I think that I’m not going to learn this language to the point of having even a modicum of self-confidence in it!’ Elza replied: ‘Look, Paulo. I’m enjoying it here, I don’t want to go back, there’s no reason to go back, and not for you either. Just be humble and study! If you take it seriously, you will speak English, as you have done other things! Assume that responsibility today! Of course I don’t believe that you came here irresponsibly, from a subjective point of view. Objectively, you really are not speaking! So work to overcome that!’ Paulo once again followed Elza’s advice.”

Sérgio Haddad holds a degree in economics and pedagogy, and a PhD from the University of São Paulo (USP). A former professor in the Postgraduate Program in the Education of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP) and of the University of Caxias do Sul, he is currently participating in the coordination of the NGO Ação Educativa. A senior CNPq researcher, he recently released the book O Educador: um perfil de Paulo Freire published by Todavia.

*The cited passage is an excerpt from O educador, um perfil de Paulo Freire.

“Paulo Freire – You actually have to learn to make the difficult business of rupture that exile implies. And to live precisely, dramatically, the ambiguity of being and not being that exile poses.

You have to assume the context of borrowing and, inasmuch as you do it with clear vision, it enables you to one day, sooner or later, return to your context of origin. You have to assume it without anger, lucidly, emotionally balanced.

At a certain moment, the context of borrowing might seem to you as though it were a pure “marquee” under which you wait for the rain to stop. It is necessary, however, that you be aware that exile is more than the marquee under which you take shelter. If you do not go beyond the figure of the marquee you could one day dramatically perceive that you define yourself by having done nothing while you waited for the rain to stop. Standing still under the “marquee,” while the rain was falling, the exiled person is like the imprisoned person that [Frei] Betto referred to: you drown in the imagination of the impossible. The exiled person who transforms the exile into a permanent “marquee” sinks into the nostalgia of his context of origin instead of experiencing the longing for it.”

(“Essa escola chamada vida,” interview of Paulo Freire and Frei Betto conducted by Ricardo Kotscho, page 54)

Seção de vídeo

Educator Paulo Freire tells about his experiences in exile, the difficulties and the learning moments, and how his encounter with his Recifeness made him become a citizen of the world. Writer Lydia Hortélio describes her experience in Bern, Switzerland, and her meeting with Paulo Freire. She also recalls the songs she sang to the educator and how those songs made the two of them identify popular games and pastimes they shared in common.

“Paulo Freire – (…) besides the affective – nearly amorous – relationship, as an exiled person you need to seek a political insertion, doing something that you believe in, doing something through which you feel you are making a contribution, as small as it may be, to some other people.

The moment you begin to deny yourself the right to be making, at any moment, value judgments, you start to learn to live a virtue that I think is politically very fundamental to this country: the virtue of tolerance. A tolerance that teaches us, overcoming the prejudices, to live with difference, and ultimately allowing us to struggle better against the opposition. This is tolerance.”

(“Essa escola chamada vida,” interview of Paulo Freire and Frei Betto conducted by Ricardo Kotscho, page 56)

by Moacir Gadotti

It is very good to show when, where, how and why Paulo Freire learned. I am a witness of how his words were not just a discourse when he stated, “No one is ignorant of everything. No one knows everything. We all know something. We all don’t know something. That’s why we always learn.” Paulo Freire learned all the time, and his learning was constructed in dialogue, seeking to know and to valorize the knowledge of the other.

I met Paulo Freire personally in Geneva, in 1974, where he was receiving many people from different parts of the world. What impressed everyone was his curiosity and willingness to listen and learn. He wanted to know what the people were doing, what their projects were, etc. He didn’t arrive giving advice in the way of ready-made, finished proposals. He would ask first. He thus began a dialogue. And he learned a lot in that process.

I also had the opportunity to work together with him during his tenure as cabinet chief of the Municipal Secretariat of Education of São Paulo, in 1989. We began the administration process by visiting schools. Paulo Freire would sit, listen patiently, ask questions, respond to questions. Sometimes, he would get somewhat impatient, because there were people waiting for us at the secretariat with urgent matters. When we left, he would say to me: “How can we be impatient after so many years of the culture of silence? They have every right to speak, and to be indignant, and it is our duty to listen.”

I would respond: “Paulo, look at how many demands they made. They need chalk, they need desks and chairs for the children, the classroom ceilings have leaks. We need to take care of all of this urgently.” Yes he would say, “We are going to equip all the schools. If the problems of the secretariat were only those of infrastructure, it would be easy to solve. But there is a greater, more complex problem: there have been 500 years of authoritarianism and centuries of slavery, consolidating the ‘culture of nonparticipation, of oppression, of injustice.’ Changing this is also urgent and necessary. We need to work on the social and human relationships so they are more dialogic, we need to create conditions for the population to ‘have its say,’ and then to make the changes with them. Everything should be in dialogue, because everything is in constant transformation, including knowledge. Everything must be in dialogue, because we are unfinished beings and we are always learning.”

That was Paulo, with whom I worked together for 23 years.

Long live Paulo Freire!

Moacir Gadotti is honorary president of Instituto Paulo Freire and a professor emeritus of the Universidade de São Paulo (USP).